Geoffrey A. Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm turns 22 years old this year. 22 years ago the internet was in its infancy, the technology landscape looked nothing like today’s hyper-connected, rapidly changing environment, and yet, the lessons from Crossing the Chasm are just as applicable today as when it was first published.

Research has shown that less than 30 percent of digital transformation projects succeed. Digital transformation is hard but living with systems and processes that don’t meet your needs is harder. There are many reasons digital transformation efforts fall short, but lack of transparency and internal communication are prevalent in many failed programs.

In my experience, Moore’s Chasm model is an ideal tool to help solve these issues, so let’s dig in.

What is Crossing the Chasm?

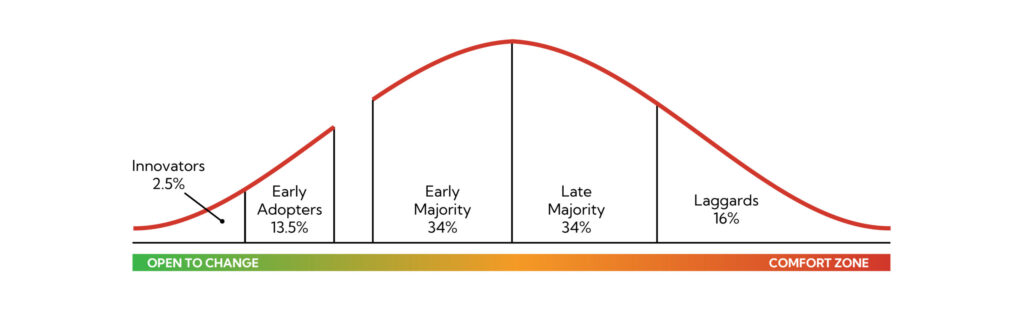

The Technology Adoption Lifecycle is a bell curve model that illustrates how groups adopt a new product or innovation. In Moore’s book, he introduces a “chasm” or a gap between early adopters and early majority, as depicted below. Without spoiling the book, it takes a significant amount of effort to create the bandwagon effect needed to move products and innovations into mainstream adoption. The risk tolerance and willingness to change for an individual considered an early adaptor is starkly different than those of the early majority, let alone late majority or even laggards.

What Chasms Do Digital Transformation Projects Face?

What Chasms Do Digital Transformation Projects Face?

One of the realizations I had while reading Moore’s book was that its lessons apply to more than just product launches. If we view the chasm as a gap between a “willingness to try something new” versus an “appreciation of how things are”, the Technology Adoption Lifecycle becomes a useful model to gain buy-in among decision makers, stakeholders, and most importantly the system end users.

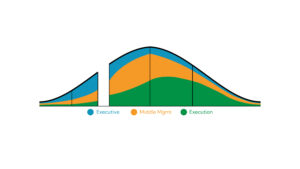

The diagram below overlays an example of stakeholder segmentation onto the Technology Adoption Lifecycle bell curve.

Stakeholder Distribution: NOTE: Each segment has representation across all five adoption groups.

- Executive Stakeholders*: Executive leaders generally show up as innovators, early adopters, or early majority. Executives have a strategic vantage point and future-focused orientation which naturally aligns them to the front of the bell curve.

- Middle Management: Be warned, this group can be little bit of a wild card. Depending on operational realities, this group may resist or jump on board early, it really depends on their individual management style, goals/objectives they need to meet, and directives coming from above. You can expect to see middle management fill the gaps between where the executives are compared to the execution layer.

- Execution Layer: Most individuals in the execution layer fall somewhere in the early or late majority as this group’s day to day role is most impacted by the adoption of new systems and technology. Their distance from the top also creates a gap in understanding of why change is necessary, distance from decision making, and lack of clarity on what’s it in for them.

*One caveat, where the CEO goes, typically the executive team follows. If the CEO is an innovator or early adopter, the executive team will find a way to follow suit. However, if the CEO is in the early or late majority, the executive team will also follow. In both cases, there are perks to being the boss.

In Practice: Improving Internal Stakeholder Alignment

Several years ago, I led a project for a small defense agency. As our scope of work increased, we were fortunate to build relationships throughout the executive, middle management, and execution layers which became invaluable when it came time to start working on a large transformation initiative.

Early on we realized executive leadership was more bought in because they had a sense of the bigger picture and a strategic understanding of why change was necessary. While executive leadership saw the advantage of a shift in focus, they weren’t personally doing the work which meant the impact to their daily role was minimal. At the beginning, we struggled to gain traction from middle management and the execution staff, as they were most impacted by the change but removed from the strategic decisions.

At the risk of implementing change without proper alignment, we quickly shifted our focus to solving execution-level problems early. By bringing in the execution staff quickly and showing the value of change to their individual roles, we were able to open communication and start to shift perspectives of largest group at the organization. Focusing on improving the experience of the individual doer gave us early momentum to ensure we were able to bridge the chasm between early adaptors and the early majority and most importantly, that the transformation stuck.

In addition to solving execution problems early, we used our relationships to empower the first movers to help federate change throughout the organization. Leveraging influential peers outside of the executive level helps gain traction across an organization as the movement feels more grassroots than top down. Digital Transformations are much more likely to stick when the heaviest users of the tools, have direct input and benefit from improvements.

The chasm doesn’t seem so big when you are able to quickly demonstrate value to the masses supported by a rock-solid case for change.